What. Is. Going. On. Here.

A quick search turned up this article (quoted below) by Greg Young of the excellent podcast Bowery Boys: New York City History.

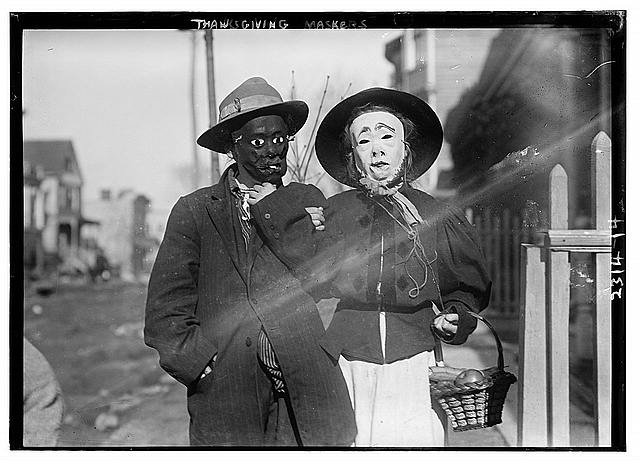

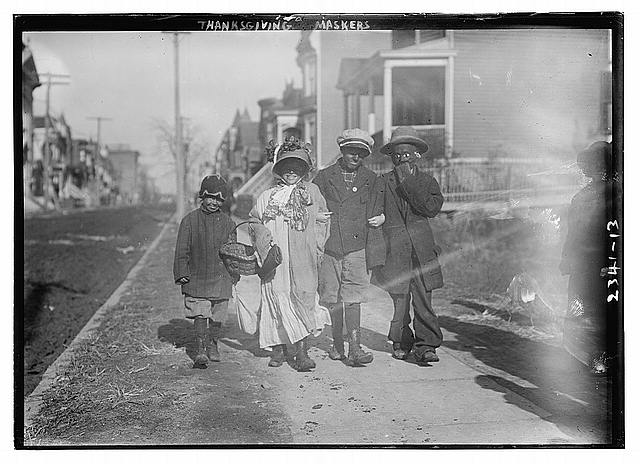

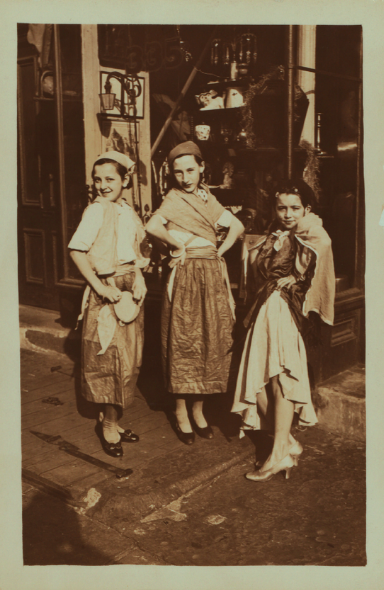

[A]n old custom from over a hundred years ago, especially popular among poor New York City children, might scare the stuffing out of a Thanksgiving dinner party today. Imagine opening your home to invited guests, only to find a group of children in wretched and unsettling disguises, disfigured masks and poverty-inspired costumes, knocking at your door and begging for sweets.

Thanksgiving ‘masking’, as it was often called, stemmed from a satirical perversion of destitution and the ancient tradition of mumming, where men in costumes floated from door to door, asking for food and money, often in exchange for music. In the 19th century, makeshift Thanksgiving parades — fantasticals — featured New Yorkers marching through the street in garish costume, most likely inspired by Guy Fawkes Day. By the late 19th century, these had morphed into a day for children to take to the street in ragamuffin garb, going from door to door, begging for fruit, candy and even pennies.”

Dressing in girl’s clothing — perhaps the most accessible ‘costume’ for many boys — was among the most popular options. According to Appleton’s, boys “tog themselves out in worn-out finery of their sisters” and spent their afternoon “gamboling in awkward mimicry of their sisters to the casual street piano.”

The key was to look as disheveled and homely as possible, an almost perverse custom given the poverty in many sectors of New York at this time. A 1910 book called Little Talks For Little People spelled out the dress code: “Old shoes and clouted upon your feet, and old garments upon you. Clouted means patched.”

Here’s a digitized (and colorized) home movie of some ragamuffins doing their thing.

This says something about not only the importance of photographing your traditions, but also the necessity of writing contextual information about them. In Buzzfeed style listicles of “Creepy Halloween costumes of the past,” outfits that now look like Thanksgiving masks (to me at least) are lumped in with Halloween. Maybe there are more Thanksgiving masker pictures out there, but they are simply misidentified, even within family collections?

One way to keep contextual information with photos, even digital photos, is to make use of metadata. This embeds information within the image file, and keeps it together — it’s the digital equivalent of writing on the back of a printed photo!

More on this later. In the meantime, don’t forget to document your own traditions! You never know what we do now that will be totally bizarre to future generations!