Around this time last year I was chatting with a friend and client about her selling her house. She was giving me her slides to scan as part of the long cleaning-out process. She had been working on it for a while and thought she had removed enough of her personal items for the realtor to being showing it. When the realtor came over to look, she said, “No no, ALL of these photos have to be removed.”

I asked if there were a lot, and she said no, just a couple. But the realtor said they all have to be gone because potential buyers won’t think of the home as available with other people’s photos in them. Like, the home hasn’t been emotionally or psychically vacated yet.

I said, “Are photographs THAT powerful?”

The short answer is YES.

In his book Camera Lucida, French philosopher Roland Barthes ruminates on the facets of Photography (big-P photography, so the nature of the medium, what makes it unique among other arts or methods of representation or communication). Over the course of the book, one theme that he returns to asks the same question: what is it about the nature of photographs, specifically snapshots, that imbues them with such an arresting power?

One quality is that photographs represent the “real.” Barthes writes “In Photography I can never deny that the thing has been there. There is a superimposition here: of reality and of the past.” (76) In other words, (in most cases) for a person or object to appear in a picture, they must have been standing in the place as it is recorded by the photo. It is this quality of photography that makes it tempting to talk about a photograph as “truthful” or a “window.” But we know that’s not quite truthful either.

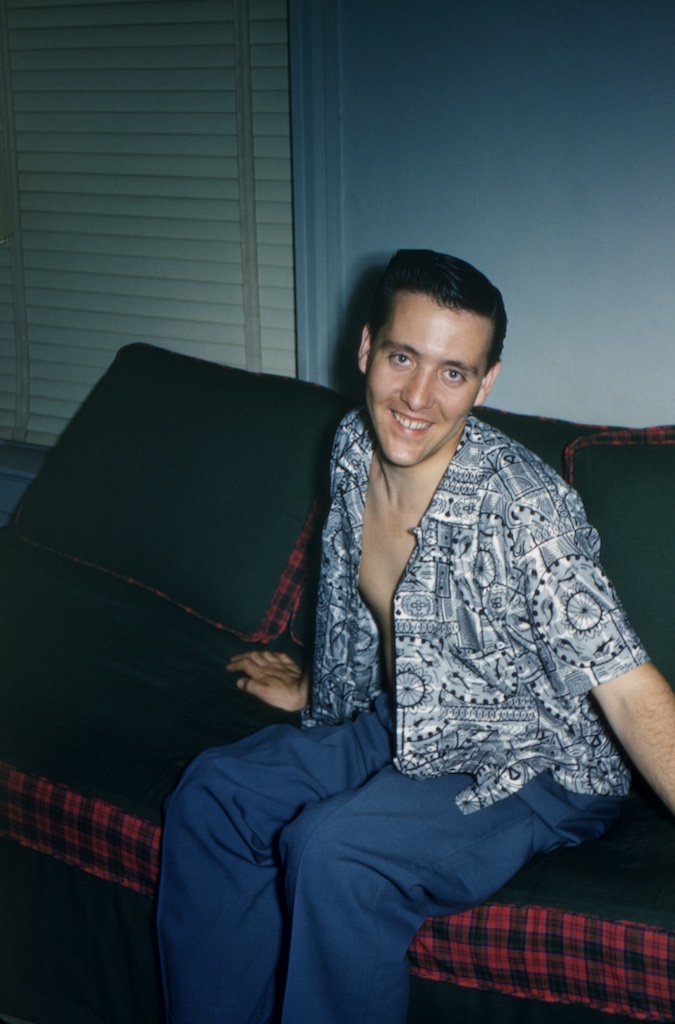

Parallel to this idea is the way photographs freeze a pose, a person, in time. “In the Photograph, something has posed in front of the tiny hole [the aperture and shutter of the camera] and has remained there forever.” (78) This person in the photograph existed here and then but not here and now—where the viewer is. The photographic moment is frozen and I think the instinct of most people, maybe especially when confronted with a picture of people they don’t know, is to extrapolate their story, to try and figure out what is going on, how their life continued after that frozen moment.

Another arresting characteristic Barthes notes is that “the Photograph has this power…of looking me straight in the eye.” We totally take this for granted! When we look at a photograph of someone we know, it’s not very weird that they’re looking us in the eye. Maybe we were the ones behind the camera that day and so the people in the photo are actually looking back at us. Or if it’s a picture of you, maybe you were looking at someone you know and love who was taking the picture. When you know the subject, it’s not so strange. But when it’s someone you don’t know in the picture looking at you directly and familiarly, it feels strange, maybe even uncomfortable! A pointed and intimate gaze from someone in the photograph is almost embarrassing, like they know all our secrets. That gaze bridges the time between when the photo was taken and when we look at it, again collapsing the past and the present.

What all of these quotes from Camera Lucida reveal is that photographs are unique in that they can be concrete representations of the past, unique in the present. A snapshot combines two time periods. The person in the snapshot exists in the past, in that fraction of a second when the shutter was pressed. They look out from the past at you in the present. Remember when film had to be developed and printed and you had to wait days or even longer to see your photos? Anything you photographed was automatically of the past by the time you experienced looking at the images, whether it was recent or distant. And photographs are always objects of the present because they exist to be looked at by you and I.